Why Construction Projects Keep Failing: Insights from Qualitative Research

- Violet Swierkot

- 3 days ago

- 6 min read

Introduction

Construction projects across the globe continue to experience chronic cost overruns, schedule delays, quality shortfalls, and, in extreme cases, complete project collapse. Despite decades of advancements in project management tools and contractual frameworks, failure remains a persistent feature of the industry. Traditional explanations have often focused on technical complexity; however, growing qualitative research suggests that construction failure is fundamentally driven by financial fragility, weak governance, behavioural bias, social dynamics, and systemic misalignment between stakeholders.

Recent studies across infrastructure and healthcare construction highlight that project failure is rarely the result of a single mistake but rather emerges through interacting organisational and decision-making processes. From flawed procurement strategies and optimistic forecasting to ineffective leadership and cultural tensions on site, qualitative investigations provide critical insight into how project environments evolve toward underperformance and collapse (Flyvbjerg, 2014; Love & Ika, 2021; Patel, 2010).

This article synthesises qualitative research approaches and key findings from contemporary construction project failure literature, demonstrating how organisational behaviour and governance structures, rather than technical challenges alone, underpin persistent project mis-performance.

Research Methodologies in Construction Failure Studies

Qualitative and mixed-method research dominates contemporary investigations into construction project failure due to the complexity and socio-technical nature of project environments. Case study methodology is particularly prevalent, enabling researchers to examine real projects over extended periods and explore decision-making processes in depth. For example, Patel analysed multiple NHS PFI hospital schemes through semi-structured interviews with senior project leaders, revealing how governance structures directly influenced cost control, stakeholder coordination, and project viability. The comparative case approach enabled identification of governance failures as a primary driver of project abandonment and financial breakdown. Similarly, Love and Ika employed illustrative case studies of mega-hospital projects to reconstruct project trajectories using sense-making theory. By tracing how early scope changes, risk misjudgement, and optimism bias escalated into major overruns, the researchers demonstrated how failure accumulates through managerial responses to uncertainty rather than technical obstacles alone. Ethnographic methods have further deepened understanding of construction failure by capturing daily operational realities. Oswald et al. embedded a researcher for three years within a multinational construction joint venture in the UK, observing safety practices, leadership behaviours, and workforce interactions. This immersive approach uncovered how regulatory non-compliance, cultural differences, weak leadership engagement, and poor worker welfare systematically undermined safety performance and organisational control systems — factors rarely visible in survey-based research.

In addition, systems-thinking approaches have been applied to model dynamic failure processes. Omotayo et al. combined professional interviews with causal loop diagramming to illustrate how project complexity, stakeholder conflict, rigid cost targets, and poor communication reinforce cycles of delay and performance deterioration. This qualitative modelling approach highlights failure as an evolving system rather than a discrete event. Root cause investigations also integrate expert knowledge within structured analytical frameworks. Shahhosseini et al. used Fault Tree Analysis supported by expert judgement to isolate causal chains leading to project failure, validating these findings through real case examples. Despite the inclusion of fuzzy logic tools, the core strength of the research lay in the qualitative interpretation of practitioner experience, which consistently pointed to financial instability and flawed procurement practices as dominant failure triggers.

Key Findings: Why Construction Projects Fail

Financial Fragility and Flawed Procurement Decisions

Qualitative root-cause studies consistently identify financial instability as the primary trigger of construction project failure. Poor cash flow management, delayed payments, unrealistic cost estimates, and lowest-price contractor selection undermine project viability from the outset. These financial weaknesses frequently generate cascading effects, including resource shortages, programme delays, disputes, and compromised quality, ultimately threatening project completion and economic justification

Weak Governance and Ineffective Decision-Making Structures

Inadequate governance frameworks significantly contribute to project mis-performance by creating fragmented authority, unclear accountability, and slow risk response mechanisms. Case studies of large NHS hospital projects demonstrate that ineffective governance leads to conflicting stakeholder priorities, delayed decisions, and loss of financial and schedule control, while robust governance structures enable adaptive management and improved project resilience

Behavioural Bias and Unrealistic Project Forecasting

Behavioural influences, particularly optimism bias and strategic misrepresentation, systematically distort early project planning and approval processes. Qualitative synthesis of global megaproject evidence shows that costs are routinely underestimated and benefits overstated, producing selection of high-risk projects that are structurally predisposed to failure. These cognitive and institutional biases embed failure conditions long before construction begins.

Deficiencies in Technical Project Management Competence

While organisational and behavioural factors shape project risk environments, qualitative studies also reveal that insufficient technical PM skills significantly amplify failure outcomes. Root cause analyses identify poor planning, weak scheduling, inadequate risk management, ineffective cost control, and flawed contract administration as recurring contributors to time and cost overruns. These technical shortcomings often prevent early detection of emerging problems and limit the project team’s capacity to respond effectively to uncertainty and complexity.

Further, hospital project case studies illustrate how scope changes, failure to manage interdependencies, and inability to adapt to evolving risks frequently reflect limitations in technical project management capability within complex delivery environments.

Social, Cultural, and Workforce Dynamics

Organisational culture and human factors play a critical role in shaping project outcomes. Ethnographic evidence from multinational construction projects reveals that leadership disengagement, cultural misunderstandings, regulatory non-compliance, and poor worker welfare create unsafe practices and undermine operational control systems. These social pressures often encourage risk-taking behaviour and suppress early reporting of problems, accelerating project deterioration.

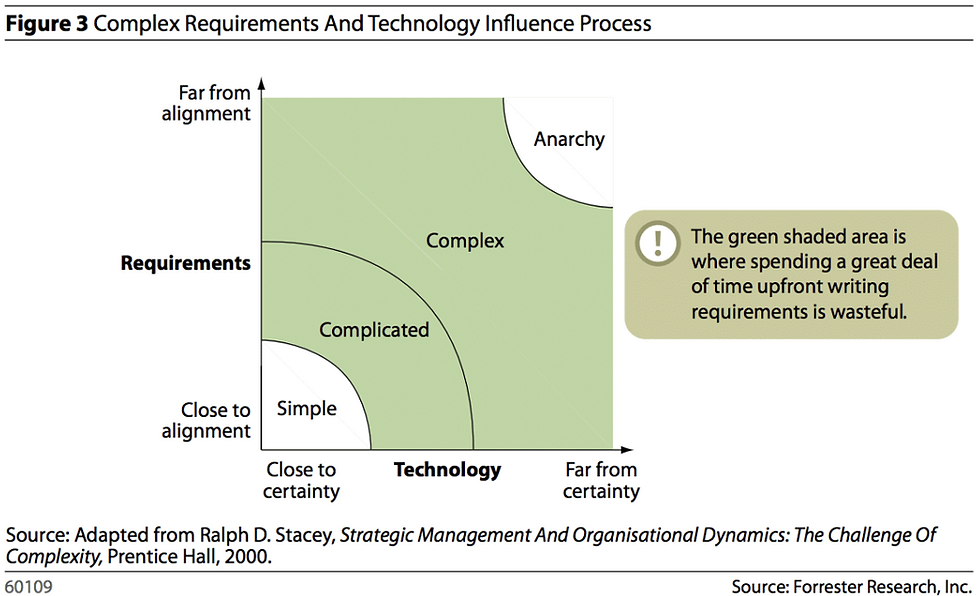

Rising Complexity and Stakeholder Misalignment

Increasing technical and organisational complexity magnifies failure risks when stakeholder engagement is weak. Systems-thinking research demonstrates that rigid cost pressures, governance constraints, communication breakdowns, and adversarial relationships reinforce cycles of conflict and performance decline. Without effective coordination and adaptive management, complexity evolves into systemic failure rather than manageable uncertainty.

Integrated Insight

Construction project failure emerges from the interaction between fragile organisational systems and insufficient technical project management capability. Financial and governance weaknesses create high-risk environments, behavioural bias distorts early decisions, social dynamics undermine control, and poor technical execution allows problems to escalate into large-scale project breakdown.

Conclusion

Qualitative research consistently demonstrates that construction project failure is not driven primarily by technical complexity but by systemic financial fragility, weak governance, behavioural bias, social dynamics, and unmanaged stakeholder relationships. Through case studies, ethnographic inquiry, expert judgement, and systems modelling, scholars reveal how early strategic decisions, distorted forecasting, poor leadership engagement, and organisational misalignment generate reinforcing cycles of cost escalation, delay, and performance breakdown (Patel, 2010; Oswald et al., 2018; Omotayo et al., 2024; Flyvbjerg, 2014).

However, while organisational and behavioural factors dominate failure narratives, the literature also indicates that deficiencies in technical project management competence amplify these systemic risks. Root cause analyses highlight poor early planning, inadequate scheduling, ineffective risk assessment, weak cost control, and flawed procurement processes as recurring contributors to failure outcomes (Shahhosseini et al., 2018). Similarly, hospital project case studies demonstrate that scope mismanagement, inability to adapt to emerging risks, and ineffective control systems often stem from limited technical PM capability within complex project environments (Love & Ika, 2021).

Taken together, the evidence suggests that construction project failure emerges from the interaction between weak organisational systems and insufficient technical project management skill. Governance failures, behavioural bias, and social complexity create high-risk project conditions, while poor technical execution—such as inadequate planning, forecasting, coordination, and control—allows those risks to escalate into tangible cost overruns and delivery collapse. Effective project delivery therefore requires not only strong leadership, governance, and stakeholder management but also robust technical PM competence embedded throughout the project lifecycle.

Ultimately, improving construction performance demands a balanced integration of technical project management expertise with organisational intelligence, behavioural awareness, and adaptive governance structures. Without this dual capability, projects remain vulnerable to both strategic misjudgement and operational failure.

References

Flyvbjerg, B. (2014) What You Should Know About Megaprojects, and Why. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gillett, M., Henderson, D. and Krishen, P. (2025) ‘Carillion’s Fall: Accounting for Construction Projects’, Accounting Perspectives, 24(4), pp. 927–945. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3838.12407

Love, P.E.D. and Ika, L.A. (2021) ‘Making sense of hospital project misperformance: Over budget, late, time and time again—why? And what can be done about it?’, Engineering, 12, pp. 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2021.10.012

Omotayo, T.S., Ross, J., Oyetunji, A. and Udeaja, C. (2024) ‘Systems thinking interplay between project complexities, stakeholder engagement, and social dynamics roles in influencing construction project outcomes’, SAGE Open, 14(2), pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440241255872

Oswald, D., Sherratt, F., Smith, S.D. and Hallowell, M.R. (2018) ‘Exploring safety management challenges for multi-national construction workforces: A UK case study’, Construction Management and Economics, 36(5), pp. 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2017.1390242

Patel, M. and Robinson, H. (2010) ‘Impact of governance on project delivery of complex NHS PFI/PPP schemes’, Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction, 15(3), pp. 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/13664381011087489

Shahhosseini, V., Afshar, M.R. and Amiri, O. (2018) ‘The root causes of construction project failure’, Scientia Iranica, Transactions A: Civil Engineering, 25(1), pp. 93–108. https://doi.org/10.24200/sci.2017.4178

Wu, C., Brookes, N., Unterhitzenberger, C. and Olson, N. (2023) ‘The role of lean information flows in disaster construction projects: Exploring the UK’s Covid surge hospital projects’, Construction Management and Economics, 41(10), pp. 840–858. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193.2023.2210693

Comments